The Lenape

Long before the Dutch arrived, this place was part of the Lenape homelands.

The National Parks of New York Harbor Conservancy acknowledges that Federal Hall National Memorial is situated in Lenapehoking, the homeland of the Lenape diaspora, and recognizes the longstanding significance of these lands for Lenape nations past and present. Today, New York City, called Mannahatta by the Lenni-Lenape people, has the largest urban Native population in the United States, and historical awareness of Indigenous exclusion and erasure is critically important both to them and to all Americans. At Federal Hall we are committed to raising this awareness through our exhibitions and programs.

Manhattan Island in the Sixteenth Century, from the Memorial History of New York, 1892. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library.

Dutch Roots

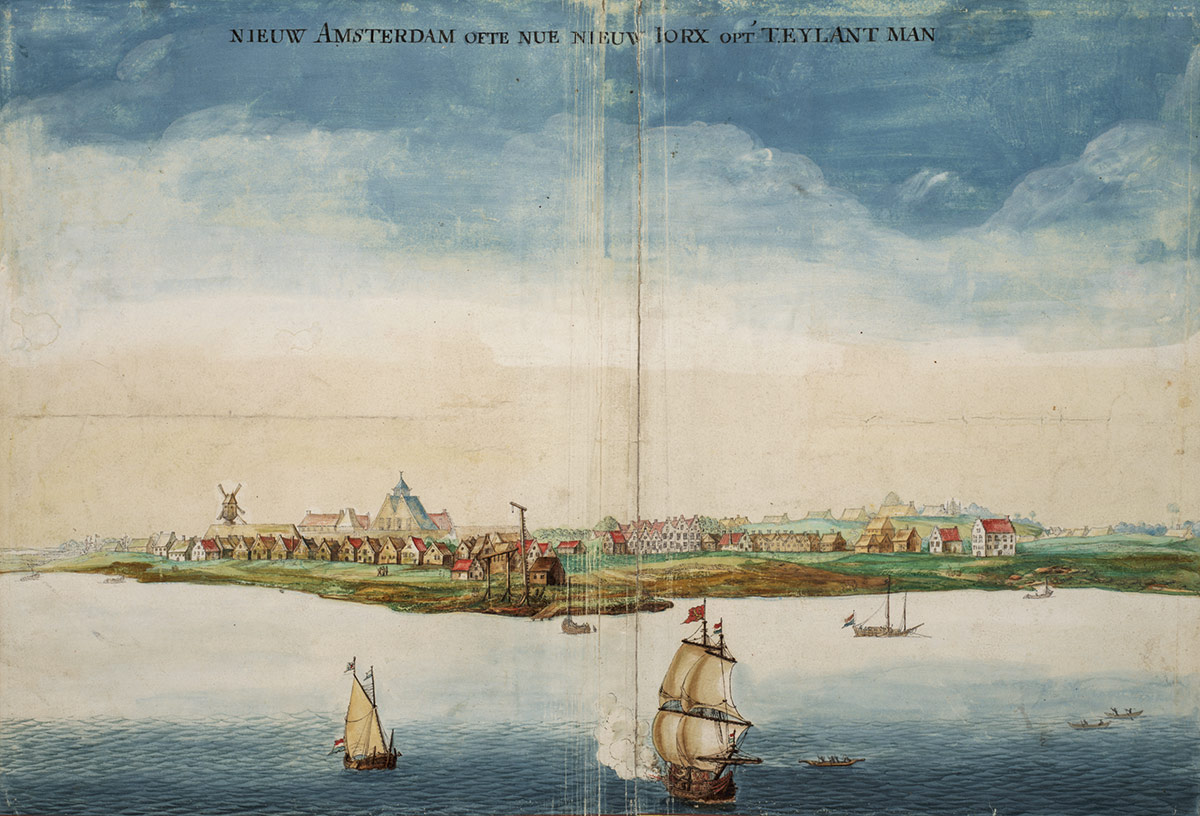

New York City is almost four centuries old. It was established as a colony in 1624 by the Dutch West India Company on what is perhaps the greatest natural harbor in the world. Then called New Amsterdam, the settlement was ideally positioned for trade, not only across the Atlantic with Europe but also by river towards Canada.

View of New Amsterdam. Johannes Vingboons, 1664. Nationaal Archief, The Hague, The Netherlands.

Purchase of Manhattan Island by Peter Minuit. Unidentified artist, 1939. Collection of the New-York Historical Society.

The entrepreneurial trader Peter Minuit gathered Dutch settlers and traders into a consolidated community at the tip of Manhattan to form a stronger and safer settlement.

A famous historical legend claims Minuit negotiated the ‘purchase’ of the island from the Lenape for 60 guilders worth of goods—calculated in the 19th century to be $24. Modern historians believe that the Lenape did not consider this transaction a sale, but only that it marked an alliance. They did not expect they would be displaced from their lands.

Within only two decades, newcomers from all over the world had moved to New Amsterdam forming a bustling port town. One visitor counted as many as 18 languages spoken.

Such ethnic diversity brought with it a multiplicity of religions, and New Amsterdam, probably more than any other North American colony, generally tolerated pluralism for several reasons. Their tolerance was rooted in the history of violent oppression in Dutch provinces by the Spanish Inquisition during the 16th century. Religious tolerance also aligned with Dutch commercial interests. After all, the settlements of the Dutch West India Company were first and foremost trading posts. The company believed nothing, including religious disputes, should ever hinder trade. Dutch tolerance set a precedent for religious freedom later enshrined in the First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States.

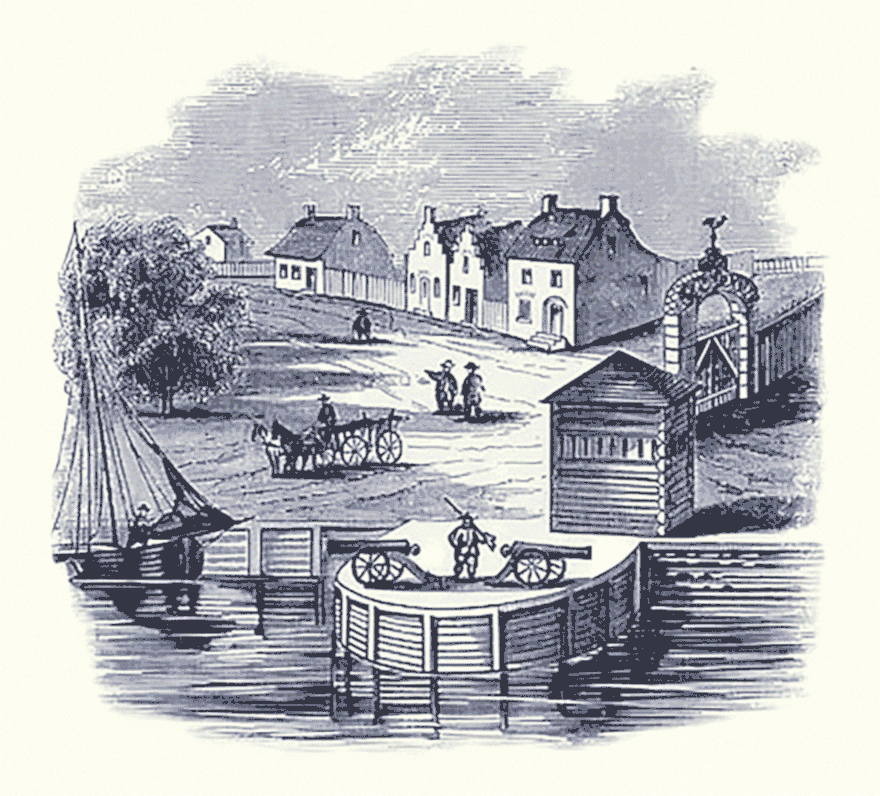

View of the wall and water gate, at the foot of Wall Street. The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library.

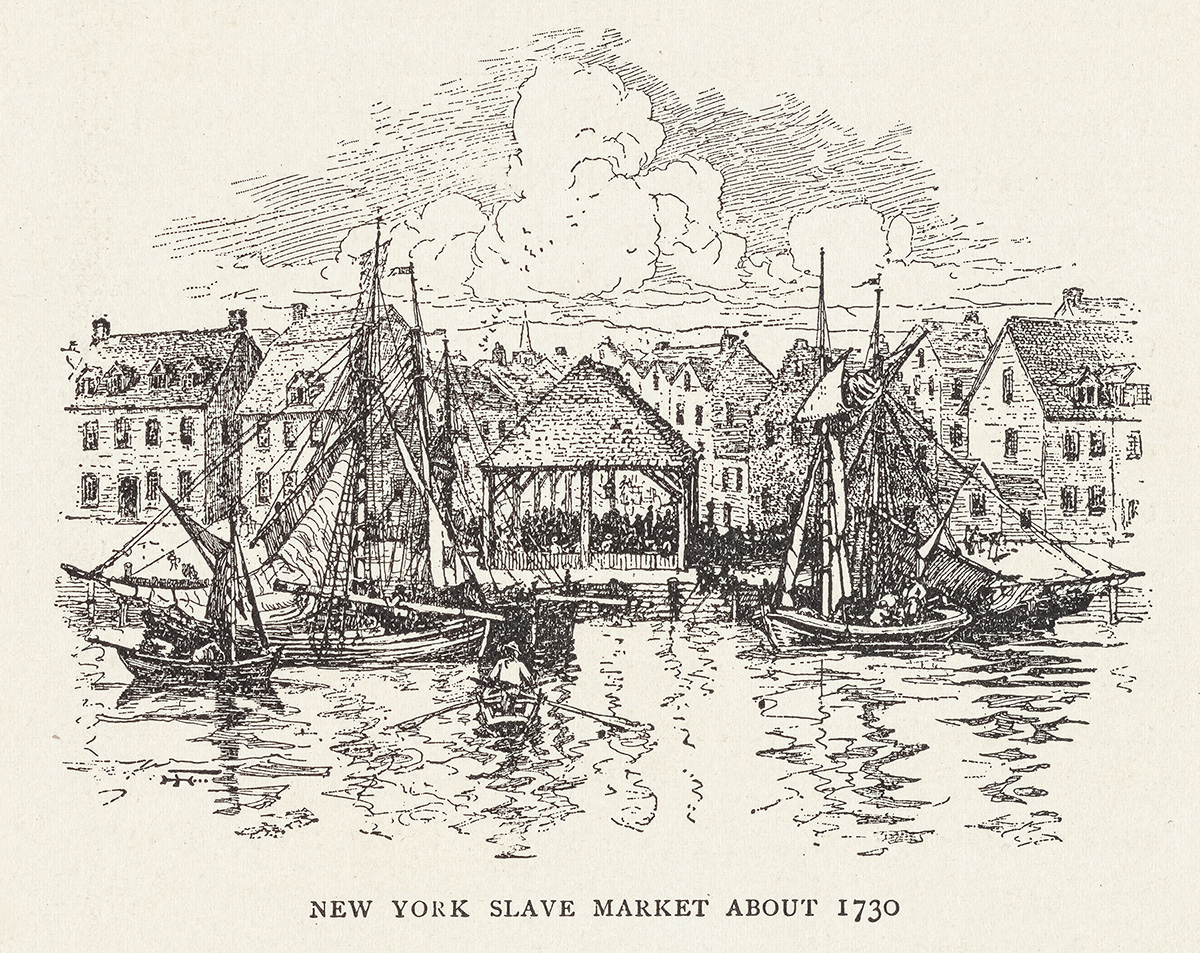

Slavery in New York

Not everyone was tolerated. The Dutch also introduced slavery to New Amsterdam. Privateers for the Dutch West India Company raided ships, captured their cargo of Africans, and delivered these people to New Amsterdam.

In New Amsterdam they were called “the company slaves,” and used on public works projects that improved the growing colony. Enslaved people built the wooden palisade on Wall Street in 1653, where Federal Hall was later constructed, as well as fortifications along the harbor. Many of the Black people had valuable skills, and some were permitted a measure of opportunity and freedom under Dutch rule that would later vanish.

Lucrative trade routes made the thriving port of New Amsterdam a target. In the late 17th century, the English wanted to expand their toehold on the shores of the New World beyond their first colonies in Virginia and Maryland. New Amsterdam was in their sights.

English Colony

In 1664, the English King Charles II sent four ships prepared for battle to New Amsterdam. The Dutch colonists, none too happy with their own authoritarian director-general, Peter Stuyvesant, surrendered without firing a shot.

The city was renamed New-York after the king’s brother, the Duke of York, who had led the invasion. For more than a century the English ruled their prosperous colony, but the seeds of the new nation were already being planted. Dutch influence endured. English governors saw no need to interfere with a profitable town, and so the vigorous pursuit of trade and a tolerant immigrant culture that had taken root in New Amsterdam continued unimpeded. This legacy ensured that as the city developed under English rule, it became a very different place from Boston or Philadelphia where Puritan and Quaker settlers had traveled to escape religious persecution. The cultural homogeneity they brought with them largely remained the norm in those cities.

Peter Stuyvesant, in 1664, standing on shore among residents of New Amsterdam who are pleading with him not to open fire on the British who have arrived in warships waiting in the harbor to claim the territory for England. The fall of New Amsterdam. Jean Leon Jerome Ferris. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Andrew Hamilton defending John Peter Zenger in court. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

English governors ruled the colony from the New York City Hall built on Wall Street in the same location where Federal Hall now stands.

Peter Zenger, a printer who published the New York Weekly Journal, wrote a series of articles critical of a recently arrived royal governor. Incensed, the governor had Zenger arrested for libel. The famous trial of the printer-publisher Peter Zenger was held at the City Hall in 1735. The court determined that you cannot be found guilty of libel if what you are printing is the truth. This important decision laid a marker for freedom of the press in the English colonies and presaged the American judicial system that would evolve at Federal Hall decades later.

Slavery grew in New York and so did the city’s economic ties with the cotton economy in the South. New York’s banks, financiers, shippers and insurance companies regularly did business with Southern plantation owners. By the 1720’s, New York was second only to Charleston in the number of enslaved people in the city. From 1700 to 1774, an estimated 6,800 enslaved people were admitted to New York, many to be sold at the slave market at the foot of Wall Street, just down the block from where Federal Hall now stands.

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection, The New York Public Library.

Enslaved labor was critical to the prosperity of the colony. Their forced labor built Broadway, widening what had been an Indian trail, and their skills in trades like barrel-making were essential for commerce at the port. The English codified the distinction between white freemen—including indentured servants whose labor was also bound for a set term—and chattel slavery, taking away the few rights Black people had under Dutch rule. Increasing cruelty provoked a response. The first uprisings by enslaved people took place in New York in 1712 and 1741. Both rebellions were brutally put down, with dozens of Black men, women and children executed.

Alongside the reality of slavery, throughout the colonies there was growing talk of individual rights and freedom. Short of revenue, especially after defending its American colonies during the French and Indian War, Parliament unilaterally imposed taxes on trade that were particularly damaging in New York. In 1765, a full decade before the first shots were fired in Massachusetts at Lexington and Concord, representatives from nine of the 13 colonies convened the Stamp Act Congress at Federal Hall in New York to protest against taxation without representation. The idea of a united states free from the tyranny of a distant monarch began to emerge.

War for Independence

For some people, the Revolutionary War evokes the cities of Boston or Philadelphia, but actually first blood in the war was shed in New York, nearly two months before the famous Boston Massacre in March 1770.

Not far from Federal Hall, patriots had erected a symbolic liberty pole, and British soldiers hacked it down. A scuffle escalated, and then a patriot lay dead. Accounts of casualties differed, but the confrontation was immediately immortalized as the Battle of Golden Hill. The cause of revolution had taken root in places like New York’s Fraunces Tavern, a replica of which still stands. Delegates from the colonies began to consider their alternatives. Ultimately, the Second Continental Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776.

On July 9, the first copy of the Declaration of Independence arrived in New York City. George Washington, recently established as General of a new Continental Army, had it read to his troops who were assembled on the City Commons, what is today New York’s City Hall Park.

A few weeks later, the largest armada the world would see until D-day invaded New York Harbor. Hundreds of ships delivered 30,000 troops to Staten Island where they landed unopposed. When the British Redcoats attacked, General Washington and the 9,000 troops encamped in Brooklyn were hopelessly outnumbered. In the most daring feat of the war, Washington saved the Continental Army in a muffled nighttime retreat across the East River from Brooklyn. They marched north through Manhattan and lived to fight on in a war that lasted for seven long years.

Fraunces Tavern (Old Delancey Mansion) circa 1700s.

Retreat to Victory. Henry Hintermeister, 1961. Collection of Fraunces Tavern Museum.

Representation du feu terrible a Nouvelle Yorck. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

A month after Washington escaped from New York City, a raging wind-swept fire raged through the city and burned as many as 25 percent of the wooden buildings clustered in what is now Lower Manhattan.

It remains unclear what or who started the fire, but the impact was devastating.

The British remained in New York longer than any other American city, inflicting misery and holding more New Yorkers as prisoners than patriots from any other state.

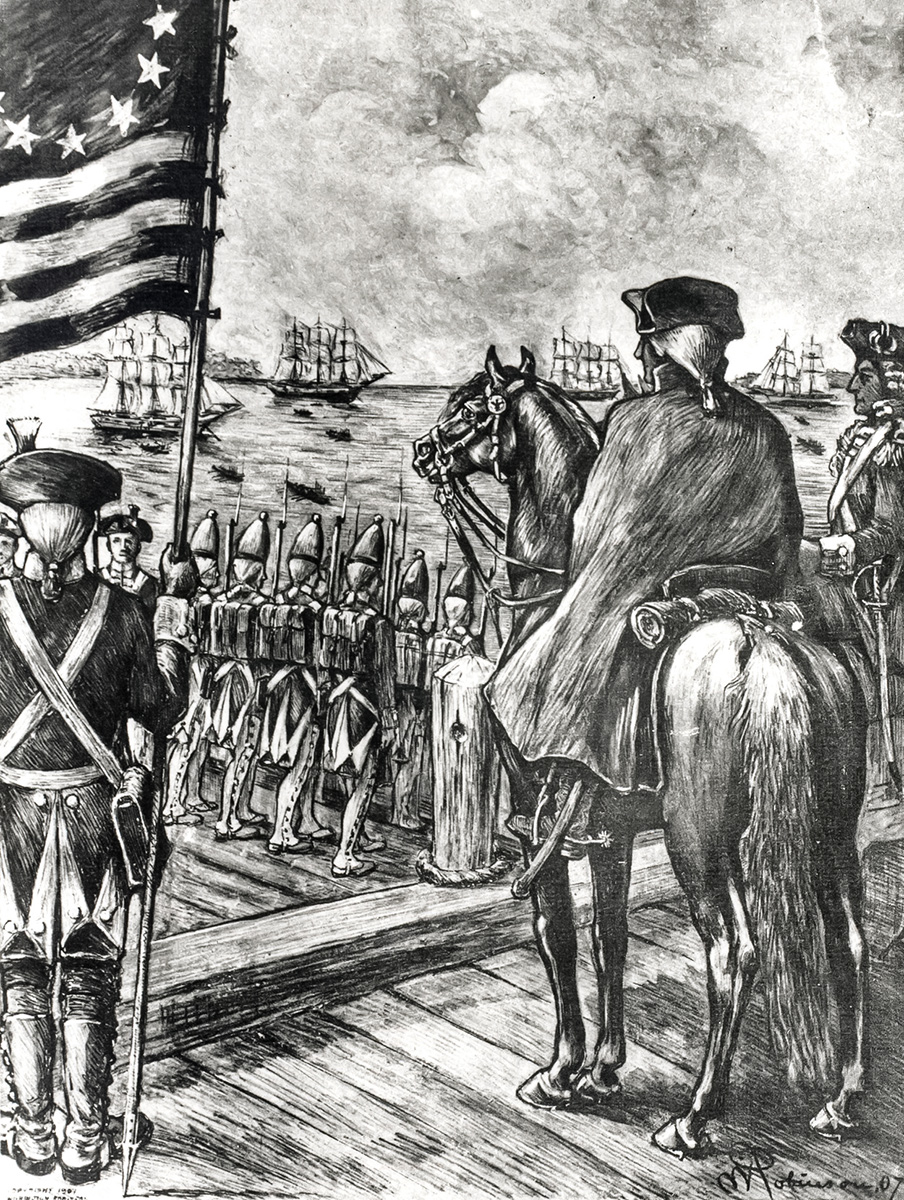

After they finally surrendered at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, it would still take two years before all the Redcoats left and the colonies were truly free. Once England finally signed the Treaty of Paris, Washington liberated New York City after seven years of occupation on Evacuation Day, November 25th, 1783. He rode triumphantly down Broadway as the last of the soldiers in New York sailed out of the harbor.

Evacuation Day and Washington’s Triumphal Entry in New York City, Nov. 25th, 1783. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

The British fleet leaving New York Harbor on Evacuation Day.

Washington was not pleased to know that the British fleet took thousands of formerly enslaved people on board their ships. As a priority in his negotiations on the evacuation with the British, Washington had reiterated the resolution of the Continental Congress demanding “the delivery of all Negroes and other property” belonging to Americans.

But the British had pledged that those who had fought and worked with them would earn their freedom. They honored that commitment. Among the “Negroes” never returned were Deborah and Harvey Squash, formerly enslaved by George and Martha Washington. They had escaped from Virginia to New York and fought for their freedom alongside the British. Many of the Black men who had joined the Continental Army were forced back into slavery after the war. While the colonies were now free, they were not.

The British fleet leaving New York Harbor on Evacuation Day.

Nine days after Evacuation Day, General Washington invited his officers to join him in Fraunces Tavern’s Long Room to thank them for their service and bid them farewell.

He resigned his commission in the military and returned to Mount Vernon as a citizen. The work of organizing a new country still lay ahead.

Washington Farewell to his Officers. Collection of Fraunces Tavern Museum.

Vision for a Nation

Now that the war was over many questions remained about how to create a new united country. The men called “the framers”—all white landowners—envisioned a nation unlike anything a world of hereditary kings and emperors had ever seen.

For more than five years after the British surrendered, delegates from throughout the former colonies met to map out a brand new system of government. They continued the work of the First Continental Congress, which had convened in the 1770s to try to find a resolution to the problems of British rule. As the adversarial situation between the colonies and the British Crown had escalated, the Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia and issued the Declaration of Independence. When war broke out, the Second Continental Congress functioned as the provisional government. It successfully managed the war, secured support from foreign nations, and drafted Articles of Confederation.

The Confederation Congress picked up the work of the Second Continental Congress to lay the foundation for this new government. George Washington travelled from his Virginia plantation, along with other delegates who left their homes and businesses, to debate a host of issues that needed to be settled to unite the very different northern states and the southern states into one united states.

The framers drafted the Constitution of the United States; the Confederation Congress submitted it to each state for ratification. Having just fought a war for independence, the states were very focused on maintaining their individual powers and regional priorities and reluctant to cede their prerogatives to a new national government.

Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States, by Howard Chandler Christy.