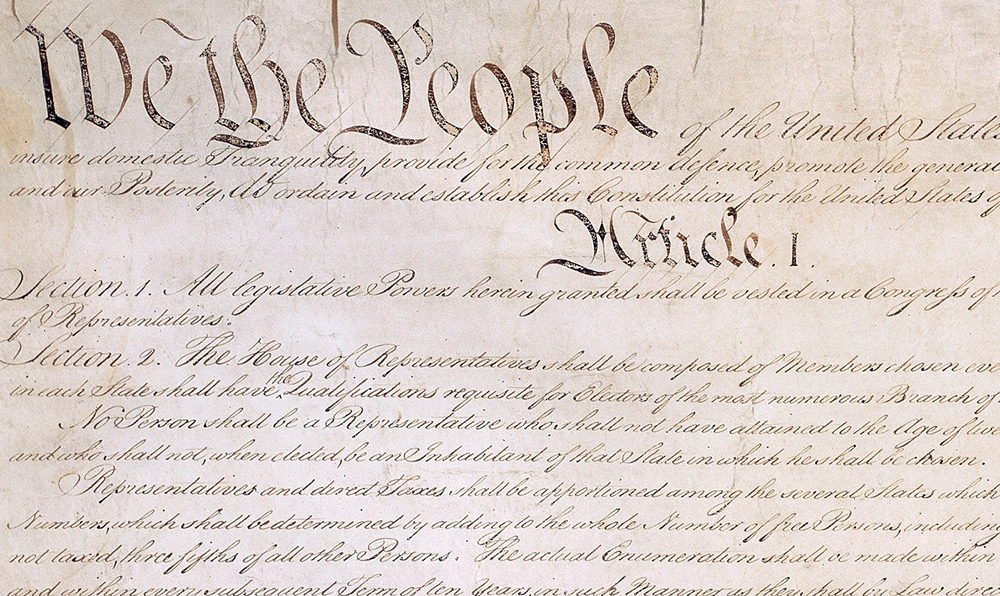

By June of 1788, nine states had ratified the Constitution, meaning that it would take effect.

The Constitution called for a President of the United States, chosen by electors, and the process of electing the first president was scheduled for the months ahead. The Confederation Congress had met in several different cities including Philadelphia, Anapolis, Princeton, and Trenton before it finally settled in New York City where it was agreed the new government would begin in March of 1789 once the states selected their representatives for the new Federal Congress.

First

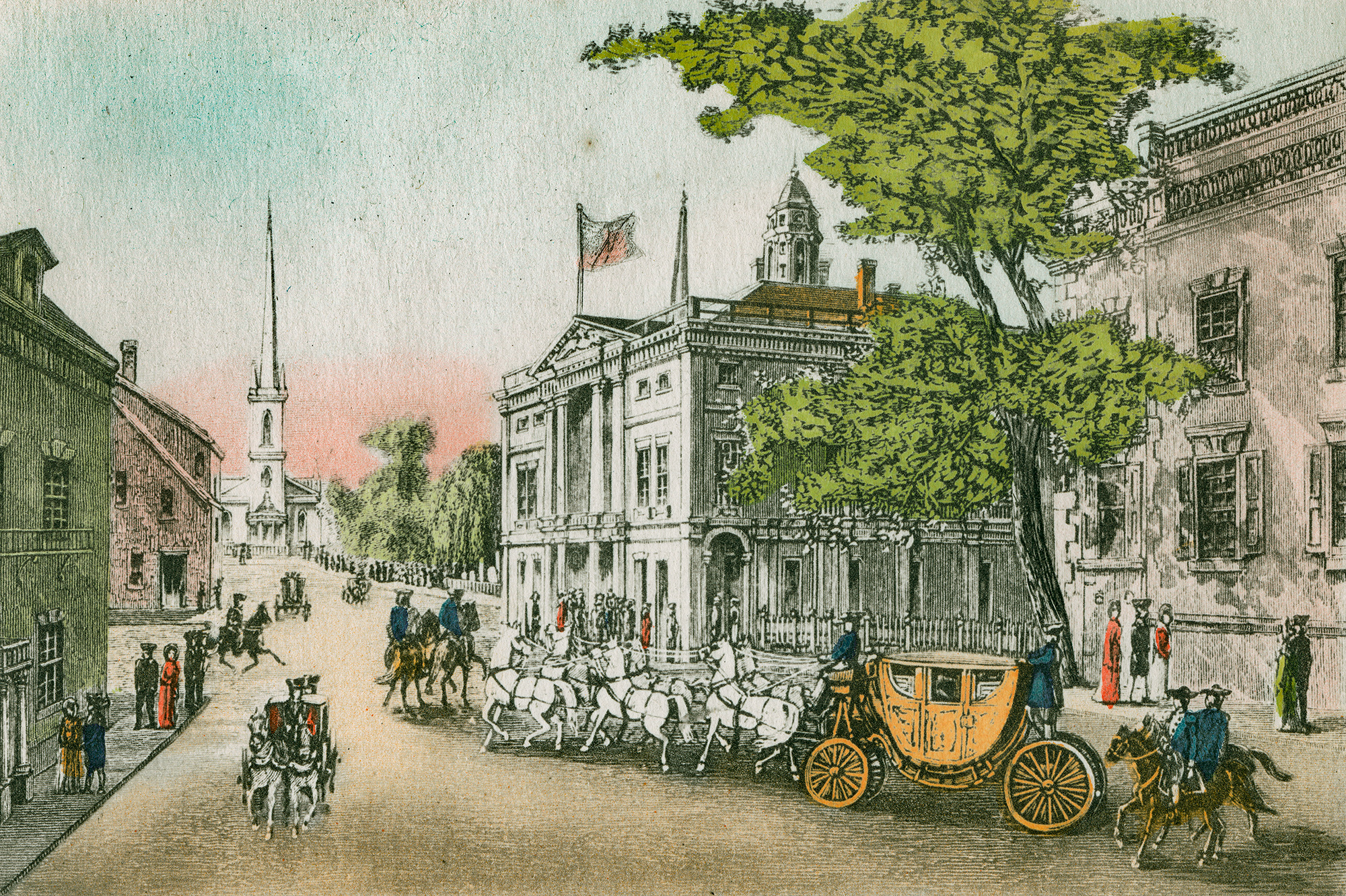

Federal Hall is a place of firsts. The United States of America, the most enduring democracy the world has known—began in New York City, the nation’s first seat of government under the Constitution at Federal Hall in 1789.

The most prolific First Congress convened and inaugurated and the great general as the First President.

A view of the Federal Hall of the City of New York, as appeared in the year 1797; with the adjacent buildings thereto. George Holland. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Federal Hall, Wall Street and Trinity Church, New York, in 1789. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The former New York City Hall was enlarged, refurbished, and renamed Federal Hall as the nation’s first capitol building. Here, the new Congress and the nation, awaited the arrival of the man who had been elected to serve as America’s first president, George Washington.

Federal Hall, Wall Street and Trinity Church, New York, in 1789. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

First President

George Washington’s Inauguration

April 30, 1789 was Inauguration Day in America. Clouds blanketed the city, but an eager public in New York City was determined to take part in a grand jubilee to celebrate the elevation of George Washington to the presidency of the United States.

“We shall remain here, even if we have to sleep in a tent,” said one visitor. New York was a city of 29,000 residents, 300 grog shops, and no sidewalks so the crowding was intense. In every window, on every roof, and in the streets a massive throng of people had gathered. At dawn, thirteen cannons roared their salute, and George Washington emerged on the portico of Federal Hall as the sun broke through the clouds. Or, so the story goes.

Washington wore a dark brown suit “of homespun clothes.” It was made in America, and the symbolism was rich to the members of the international press in attendance. The world had never seen a national leader dressed so simply – no lavish robes trimmed with fur, not even a dashing military uniform. George Washington presented himself to the people as one of them, an ordinary citizen now assuming the role of president. Washington placed his hand on the Bible and took the oath of office, the same oath that every American president has subsequently sworn to. The air exploded with cheers: “Long live George Washington, President of the United States!”

The Constitution requires that presidents must take this oath of office before they assume their presidential duties. This thirty-five-word oath prescribed in Article 2 of the Constitution formally ends one president’s term and begins the next. From the day George Washington placed his hand on the Bible and recited the oath, inaugural ceremonies have been an important symbol of the continuity and permanence of American government.

Washington attends Congress, Wall Street, 1789. Collection of the New-York Historical Society.

Inauguration of George Washington, April 30, 1789. Ramón de Elorriaga, 1889. Federal Hall collection.

A New Day at Federal Hall exhibition concept featuring the Washington inaugural Bible.

The Washington Bible

When Washington arrived at Federal Hall, someone realized that there was no Bible to use for swearing the oath and so one was hastily borrowed from the nearby St. John’s Masonic Lodge No. 1.

Under Washington’s hand, the Bible was opened to Genesis 49:13, a random choice that read, “Zebulun shall dwell at the shore of the sea; he shall become a haven for ships, and his border shall be at Sidon.” Now known as the George Washington Bible, and still owned by the Lodge, this particular Bible has been used for the inaugurations of several subsequent presidents. In 1989, the bicentennial year of Washington’s first inauguration, George H. W. Bush used this Bible to swear his oath of office. As part of New Day, plans are underway to bring the Washington Bible back to Federal Hall for public exhibition.

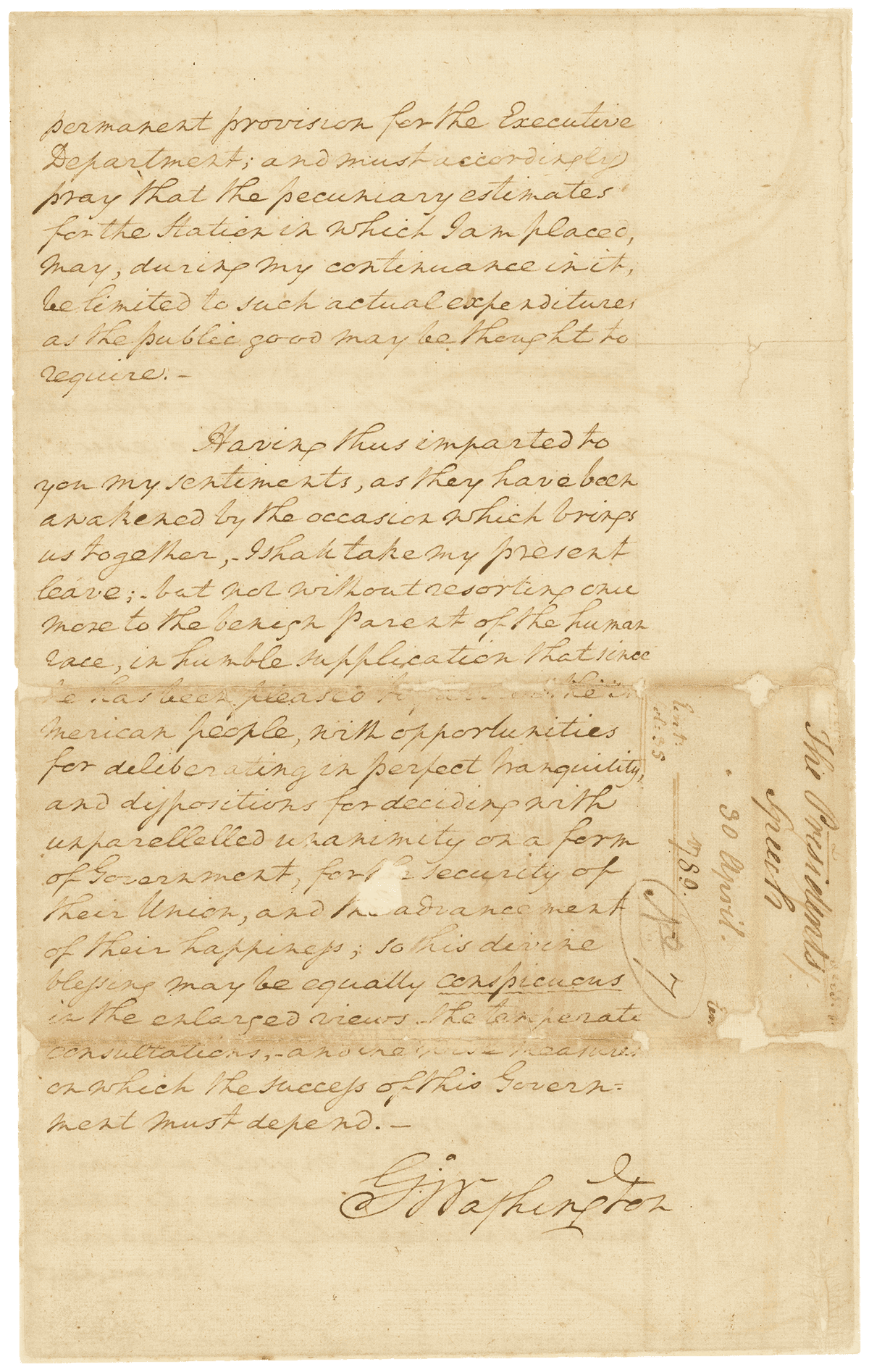

The Inaugural Address

There was never any doubt that George Washington would be the first president. He was revered throughout the new country for his heroic leadership during the war as well as for his service and measured judgment in the series of congresses that had advanced independence.

Nevertheless, the process of election specified by the Constitution took some time to unfold. In Mount Vernon, Washington waited and began to ponder what he should say to the new nation on the occasion of his inauguration. He wrote a lengthy inaugural address during these months that was filled with his thoughts and aspirations for the nation. This address was, however, never delivered. After he was sworn in, Washington and the members of Congress moved into the Senate Chamber in Federal Hall. There he delivered a much shorter inaugural address that was largely written by James Madison. In closing his brief remarks, the newly-installed President Washington put responsibility for the nation in the hands of its citizens saying “… the preservation of the sacred fire of liberty and the destiny of the republican model of government are justly considered, perhaps, as deeply, as finally, staked on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.”

George Washington’s First Inaugural Address, April 30, 1789 (final page). Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives.

Washington the Slaveowner

When Washington left Mount Vernon to travel to New York for his inauguration, his entourage included seven enslaved Blacks, including his valet William Lee, who had served him throughout the war.

Lee was such a familiar member of the Washington household, it is believed he is included in a family portrait painted by Edward Savage. Washington’s household also included a young Black woman named Ona Judge who served Martha Washington as a lady’s maid.

In Virginia the Washington’s owned approximately 200 enslaved people, a larger workforce than he oversaw in the entire fledgling federal government. Slavery was a moral issue much in dispute in the new country, and it seems Washington struggled with how to resolve it. But despite some of the reservations he expressed, he did not free his own slaves until his death. And even with that, he did not prevail upon Martha that the people she owned as slaves should be freed as well.

The issue of slavery continued to be divisive among the states, and it was at the heart of some compromises that Washington and the first Congress agreed to. These decisions would shape American history to the present day.

The Washington Family. Edward Savage, 1789-1796. Andrew W. Mellon Collection, National Gallery of Art.

Life of George Washington—The Farmer. Junius Brutus Stearns. Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

John. John Trumbull, 1790. Trumbull drawings, Fordham University Libraries.

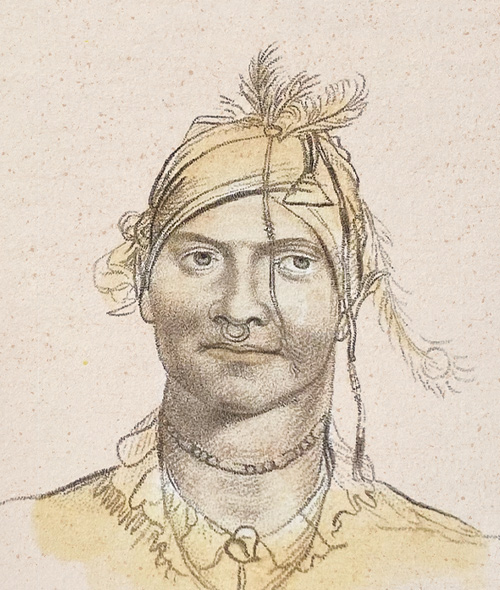

First State Visit—The Creeks in New York

The new Constitution provided that the president “shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties,” provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur. Ironically, the first international treaty that George Washington negotiated was with Native Americans who had lived on the land before it was claimed by the colonists. Alexander McGillivray was a Creek leader whose mother was Native American and whose father was Scottish. He was formally educated and raised by his father, who owned enslaved people, to know plantation life and trading. In 1790, McGillivray led a delegation from the Creek Nation who arrived for the first official state visit to New York City. The native people had travelled from the then-distant lands of Florida, and they were welcomed with celebrations and formal balls.

Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox knew that tribal sovereignty clashed with the priorities of the people living in the frontier states. They wanted to resolve any conflicts with legal diplomacy that adhered to the nation’s newly-certified republican ideals. Treaties are binding agreements between nations and become part of international law. Treaties to which the United States is a party also have the force of federal legislation, forming part of what the Constitution calls ”the supreme Law of the Land.” The agreements in the Treaty of New York signed with the Creek people were, however, short-lived. It was the first of many United States treaties with Native people that would ultimately not be honored.

Washington and Religion

When Washington toured the northeastern states early in his first term, he pointedly ignored Rhode Island, where the Constitution had not yet been adopted. In August 1790, after Rhode Island approved the document, he finally visited Newport.

After public celebrations and appearances, Washington invited several of the city’s religious leaders to meet privately with him. The small group included the warden of the Jewish Congregation of the Touro Synagogue who offered a warm address. Washington responded with a letter back to Warden Moses Mendes Seixas sent the very next day. Offering an unequivocal commitment to the continuity of the Jewish congregation, Washington confirmed the nation’s commitment to freedom of conscience as a matter of principle, not as a matter of mere toleration. The government, Washington unforgettably proclaimed, would “give bigotry no sanction.” At the time, Jewish people comprised only about 1% of the population, but people of many religious beliefs lived throughout the states. Washington believed that tolerance of all faiths was a foundation for social cohesion and national strength. He attended church regularly, but often went to services at different houses of worship. Most importantly Washington believed, along with many of the founders, that religious faith contributes to civic virtue, which is a bedrock for peace and prosperity. Religious freedom was guaranteed in the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights, but through his leadership, Washington expanded the contours of religious freedom by transforming an ideal into a communal standard that invigorated the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of religion.

Warden Moses Mendes Seixas handing his written message to George Washington in Newport, Rhode Island. Courtesy of George Washington Institute for Religious Freedom.

First Congress

The first Congress under the new Constitution convened at Federal Hall early in 1789. The 91 Senators and Representatives were all white, propertied men, but they hailed from places as different as Massachusetts seaports and Georgia plantations.

The Signing of the United States Constitution by Louis S. Glanzman, 1987. Commissioned by the PA, DE, NJ State Societies, Daughters of the American Revolution. Independence National Historical Park Collection.

Committed to their often-conflicting agendas, it fell to these delegates to transform the lofty principles laid out in the Constitution into the enduring democratic republic that is America today. The 4,500 words of the Constitution offered a framework but not many details. The word “democracy” was nowhere in the document.

For 527 days, these men debated together and lobbied privately to flesh out the structure of the new American government based on the skeletal outline defined by the Constitution, setting the benchmark for the most productive legislative session in American history. The inauguration of George Washington was one the first tasks of Congress. They also legislated procedures for the functional operation for the three branches of American government—the Presidency, the Congress, and the Judiciary—and drafted the First Freedoms—ten amendments that would be ratified and become known as the Bill of Rights.

Congress took up many other issues including slavery, the debt incurred by the states during the long years of the revolutionary war, and the permanent location of United States capital.

The American Dilemma

Slavery had been a central point of debate throughout the framing of the Constitution, it remained a contentious issue between the states.

John and James Pemberton, Philadelphia Quakers, led the first systematic lobbying campaign in American history in the capital against the slave trade. Joined by New York abolitionists, they approached representatives in the lobby of Congress, on street corners, at their homes and boarding houses, and in the taverns.

Late in his life, Benjamin Franklin had become vocal as an abolitionist, and he began to serve as president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery. In his last public act, Franklin sent Congress a petition on behalf of the Society asking for an end to the slave trade and the abolition of slavery. The petition implored Congress to “devise means for removing the Inconsistency from the Character of the American People,” and to “promote mercy and justice toward this distressed Race.”

This petition triggered the new federal government’s first, explosive national discussion of slavery in February, 1790. After representatives from South Carolina and Georgia overpowered the voices of abolition, the Congress chose to take no action on the petition and this left decisions about the slave trade to individual states. A code of silence would be strictly observed on the issue in the halls of government until the mid-1800s. Four in ten of New York households were slaveholders. Today, as many as 15,000 free and enslaved African American men, women and children are buried not far from Federal Hall, commemorated at one of New York City’s other National Park Service monuments, the African Burial Ground.

Slaves Waiting for Sale, Richmond, Virginia. Eyre Crowe, 1861.

The “Negros Burial Ground” near the Collect Pond, looking south. Late 1700s map showing the African Burial Ground in Manhattan. Wikimedia Commons.

The Grand Compromise

Other divisive issues facing the first Congress were how to establish financial stability by paying off the debts of the Revolutionary War and where to permanently place the federal capital. Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton wanted a strong federal treasury with good credit that could support the growth of the nation, but others were against centralized power.

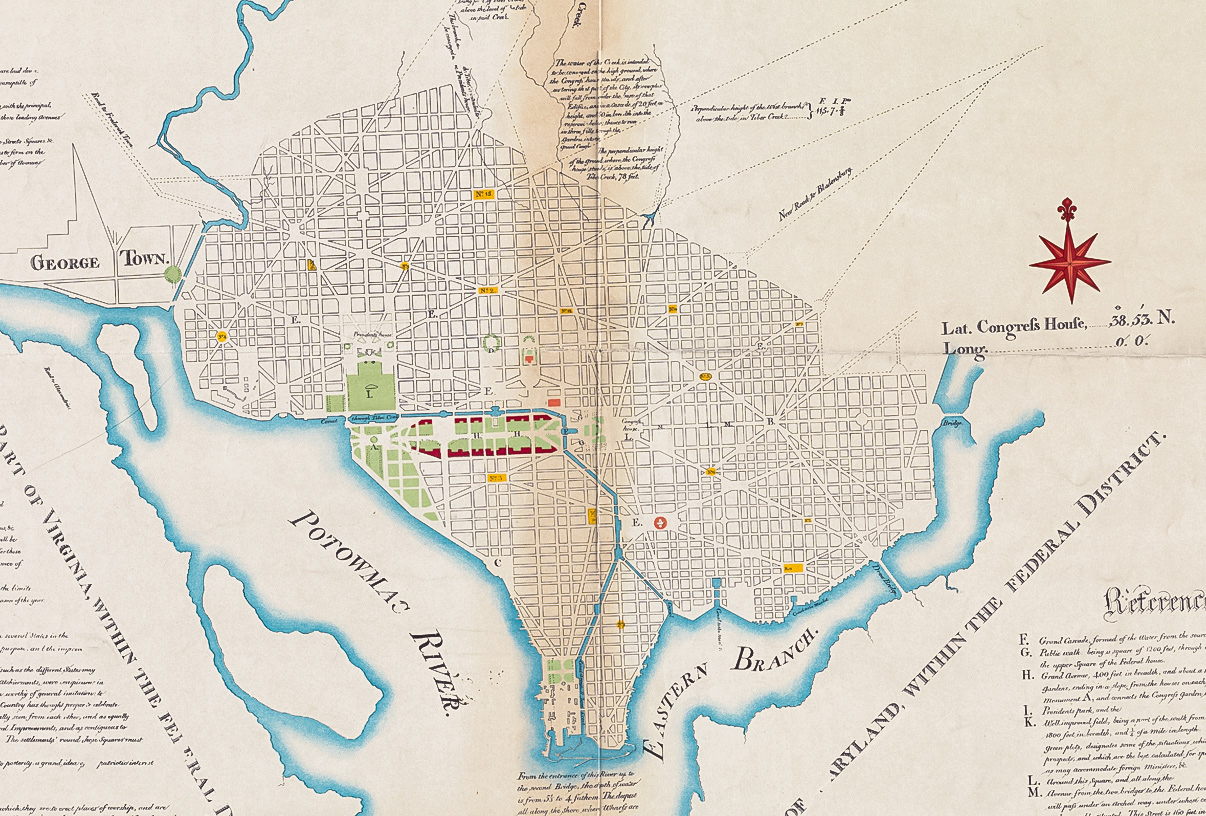

Almost every region was vying for the prestige of hosting the seat of government and the opportunity to exert influence on legislation. During fiery debates, Congress deadlocked. Hamilton broke the crippling stalemate by forging a historic bargain. Over dinner with James Madison at Thomas Jefferson’s home in Lower Manhattan, they agreed that the federal government would assume the Revolutionary War debt incurred by each state. This provided relief especially in the North where costs had been higher. In return, the seat of government moved south to the banks of the Potomac, where it was closer to Southern slave-holding states. The capital left New York first to Philadelphia for 10 years, while construction got underway for a new city on land ceded by Maryland and Virginia, with a grand neo-classical building to house Congress.

New Yorkers felt betrayed, but while their city would no longer be the nation’s capital, it thrived in decades to come as the nation’s capital of commerce.

Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of the United States… Peter Charles L’Enfant, 1791. Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library.

Alexander Hamilton’s country home—Hamilton Grange—is also a national memorial managed by the National Park Service.

It is open to visitors in Harlem.

Engraving of The Hamilton Grange. Library of Congress, by Edwin Davis French. Library of Congress.

First Freedoms

When the language of the Constitution was being debated and drafted, there was a constant tension over how powerful the new central government should be. Federalists favored a strong

national government, while Anti-Federalists wanted to put substantial limits to centralized power.

Seven of the states had included a Bill of Rights in their state constitutions, and the Anti-Federalists were concerned that the United States Constitution had not. This became an issue as the Constitution was sent to the states for ratification. While the required nine states did ratify, there was ongoing debate about the need for a Bill of Rights even as the First Congress convened, and some states continued to consider whether they would join the nation or not.

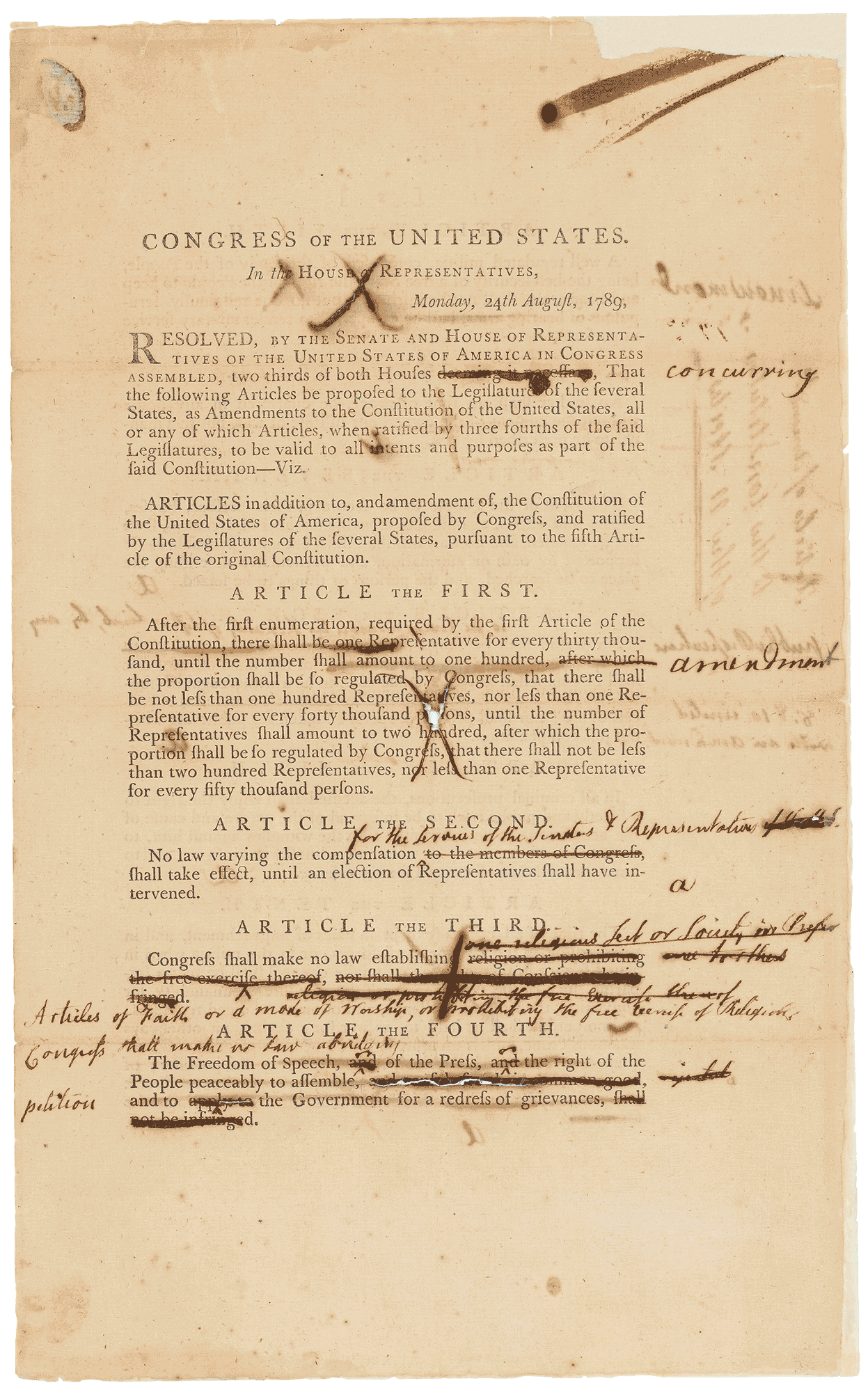

James Madison took the lead in drafting a Bill of Rights, comprised of 12 amendments, and securing its adoption. Representatives volleyed the drafts of the legislation between both houses of Congress, making comprehensive notes and edits along the way that reveal its evolution and conflicting interpretations. Ten of these amendments were eventually ratified by three quarters of the states.

The Bill of Rights defines individual freedoms of all Americans. The First Amendment, codified freedom of speech and the press, affirming a right foreshadowed 55-years earlier in the landmark trial of Peter Zenger held in New York City Hall where Federal Hall now stands. Freedom of religion, freedom of assembly, and the other freedoms defined in the Bill of Rights guarantee individual liberty. The extent of those freedoms are constantly being tested and redefined by the federal courts, often by judges who disagree over what the Framers said versus what they meant.

Senate Revisions to House-passed Amendments to the Constitution (page 1), September 9, 1789. Records of the U.S. Senate, National Archives.