Washington’s Undelivered First Inaugural Address

George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States on the balcony of Federal Hall on April 30, 1789. With that, the thirteen sovereign states that had been held together only by a “firm league of friendship,” became the United States of America. The nation was born.

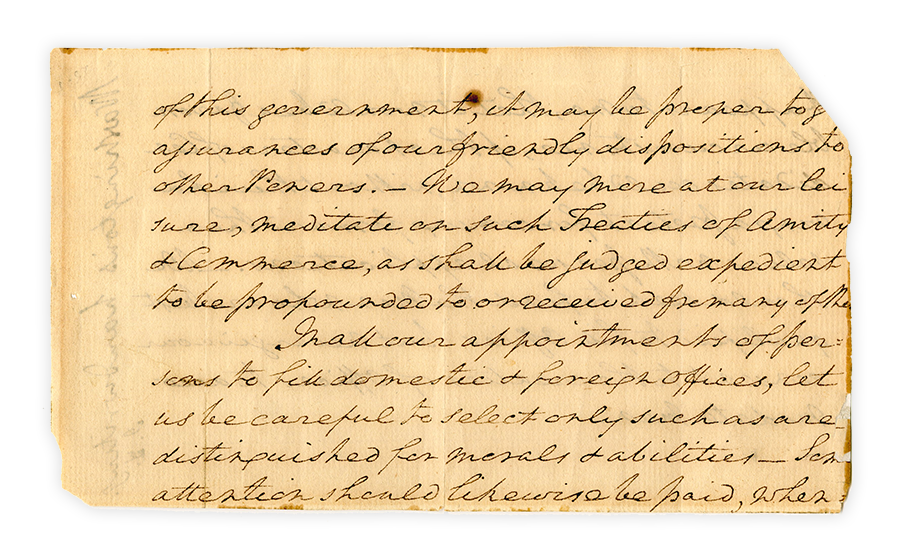

During the arduous Revolutionary War, and subsequently during the Founders’ struggle over six more years to define a way forward, Washington had formed a bold vision for this new nation. He was so revered as a national hero, it was practically a foregone conclusion that he would be selected as president. And so as the electoral process unfolded over the winter, Washington began to draft a major speech to deliver at his inauguration. There was so much he wanted to say. His former aide de camp, David Humphreys, helped him to collect his thoughts, and the result was a 73-page manuscript, written in Washington’s own hand.

But Washington never delivered that inaugural address. In fact, the manuscript has been largely lost to history until recently. The rediscovery of The Undelivered Inaugural Address is the fascinating story of a remarkable treasure hunt.

According to Dr. Kenneth Bowling, co-editor of a comprehensive history of the First Congress, Washington’s Undelivered Inaugural Address is one of his most profoundly important political statements, and it adds immeasurably to public understanding of the First President.

But first the manuscript, which has been dispersed in dozens of fragments over almost two centuries has had to be reassembled. For 30 years, that has been the quest of Seth Kaller, an expert who helps major institutions find and collect documents from America’s early history. This is the story of the hunt for The Undelivered.

The Undelivered

An interview with historian Dr. Kenneth Bowling and manuscript dealer Seth Kaller.

Q: Have you been able to hunt down all of The Undelivered?

KALLER: Well, I am still building on the accomplishments of others who started the hunt. There is a long way to go. Thirty-five pages of the original 73 are known to still exist, and I continue to collect them with purchases at auction houses and from private collectors. One fragment was offered on Ebay for $8,000! And some pieces are in other collections. For example, Princeton University has two leaves (a sheet of paper with writing on both sides). The Gilder Lehrman Collection has three leaves that I helped them acquire several decades ago.

Why didn’t Washington deliver the Inaugural Address that he wrote at Mount Vernon?

KALLER: One of Washington’s many strengths as a leader was his habit of seeking the best available advice. After he had completed his draft at Mount Vernon, he sent the Address to James Madison, coyly noting that it was “written by a gentleman under this roof.” Madison recognized this comment as signal from Wahington that he could be frank in his critique. So Madison didn’t hold back. Instead of just suggesting edits, he gave Washington an entirely new and much shorter draft that steered clear of any avoidable controversies.

Why was Madison concerned?

BOWLING: Madison feared that Congressional reaction to Washington’s very detailed speech could re-open wounds from recent ratification arguments. The colonies had fought a long war to free themselves of the British king and some of the states had yet to ratify the Constitution that brought them together into political union. These were perilous times for the new nation. There are very bold passages in Washington’s Undelivered advocating for a strong presidency and a muscular central government. Madison felt some of these views might be inflammatory to people who had fought so hard to win their independence.

So what did Washington do?

KALLER: He agreed to follow James Madison’s advice to deliver a less controversial and much shorter speech. He put his own draft aside, and it remained in his desk at Mount Vernon until long after Washington died.

Was The Undelivered really so different from what Washington actually said on his inauguration day?

BOWLING: Yes, indeed. Washington’s Undelivered Address was in essence a political manifesto that put the people first.

Did Washington believe the Constitution should never change?

BOWLING: In his oath of office Washington pledged to defend the Constitution, and he believed the Founders had done a good job in writing it. But in The Undelivered Washington described the future of the Constitution as organic, arguing that no compact devised by men “can be pronounced everlasting and inviolable.” And in fact, the Constitution has been amended dozens of times since the founding, including at the very outset by the ten Amendments approved by the First Federal Congress that are known as the Bill of Rights.

But don’t some people today say the Constitution is perfect just as it was written?

BOWLING: It is controversial. Many people hold the view that, unless an amendment is created by legislation and approved by ratification, the Constitution should be followed based on what they perceive as the original intent of the Founders. But that can be tricky. There is an abundance of historical scholarship that tries to fathom, and argue for, exactly what the original intent of the founders actually was. This view is called “strict constructionist,” and it is sometimes at the heart of Supreme Court decisions. It is not really clear what Washington himself would have thought of this approach. In The Undelivered he did urge caution about changing too much too soon before the Constitution was given a chance to operate. He wrote: “I will barely suggest, whether it would not be the part of prudent men to observe it fully in movement, before they undertook to make such alterations, as might prevent a fair experiment of its effects?”

What else was controversial?

BOWLING: In The Undelivered, Washington called for an end to slavery in America as many other countries had already done. Washington wrote that he hoped legislators “will not continue slaves in one part of the globe, when they can become freemen in another.” Abolition of slavery was already a major issue between the northern and the southern states. Ultimately, the right of the southern states to continue slavery was accepted as the price of union. Washington, a slave holder himself, freed his slaves upon his death. But Washington’s agreement with other Founders to permit slavery was fundamentally at odds with the declaration that “all men are created equal.” It took another century for President Lincoln to finally abolish it. And, of course, as a nation we are still struggling to achieve a “more perfect union” where all are truly equal in fact and in practice.

KALLER: The politics at the time were very complicated. It is important to acknowledge that Washington’s vision for America in The Undelivered was bucking thousands of years of tyrannical traditions. Despite the reality of slavery, the lack of political standing of women, and myriad other deep and often tragic injustices, he and the other Founders created the possibility of an economically and religiously diverse, multi-racial society capable of overcoming deep divisions. We are still working to fulfill that vision.

What is the longest piece and smallest fragment that you have acquired?

KALLER: The longest are the full leaves. The smallest fragment is two lines from near the beginning of the speech, and we separately acquired the next three line fragment. Even together, the five lines are still not enough for us to figure out if the fragments are from page one or from the other side of the leave, page two!